Founding Fathers - George Wythe

George Wythe

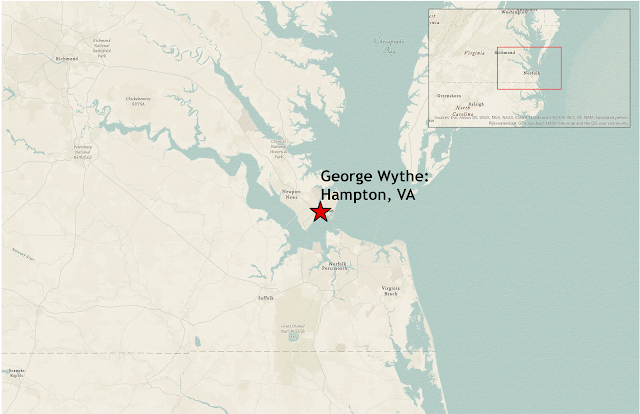

Born: ??, 1726 (Hampton, Virginia)

Died: June 8, 1806 (Richmond, Virginia)

I never cease to be amazed whenever my website hits a new milestone in visitors, and this week it surpassed 75,000. That's such a staggering number to my imagination, so thank you all for clicking on the links and checking in from time to time. This week we're turning our attention to a man who was among the most well-respected and accomplished signers of the Declaration, George Wythe. Born on the farm that had been in the family for three generations, named Chesterville, he was the second of Thomas and Margaret Wythe's three children. His father was a planter and had an ownership interest in the wharf at Hampton, the nearest town and largest port in Virginia, but he died when George was just three years old. Margaret was more highly educated than many women of the time and taught him well from the classics, while also engraining her Quaker beliefs into the young boy. As a teenager George lost his mother and became the ward of his older brother, named Thomas like his father before him, who received the family inheritance but did not care to financially support his younger siblings. After two years at grammar school George moved to Prince George County to begin studying law with his uncle, Stephen Dewey, and a prominent Williamsburg lawyer named Benjamin Waller. By 1746, at the age of 20, he passed the bar and moved to Spotsylvania to begin his legal career.

Although still a young man, the following few years were a whirlwind for George Wythe. He lived with Waller's brother-in-law, Zachary Lewis, who was serving as the King's attorney in Spotsylvania and needed Wythe to assist with his work. The two soon became family as George married his senior partner's daughter, Ann, shortly before the end of 1747. Sadly, the young bride soon became sick with a severe fever and died just seven months after their wedding. Wythe was crushed and quickly moved back to Williamsburg for a fresh start, where he devoted himself to work. Waller assisted him in finding a government position, acting as a clerk for two committees in the House of Burgesses, while the young man continued to develop his own law practice and serve as an alderman in Williamsburg. Within a few years he was appointed by the Royal Governor to take the place of the departing King's attorney but only served for a few months before being elected to represent his city in the House of Burgesses in 1755. That same year Wythe's older brother died without an heir, leaving the family estate to George, who was also newly remarried to Elizabeth Taliaferro, the daughter of a wealthy landowner from just outside of Williamsburg. Rather than returning to Chesterville, however, the couple decided to continue living in the city, where Elizabeth's father built them a new home beside the Governor's Palace. Like his brother, George would not have an heir as his only child with Elizabeth died in infancy.

While George Wythe's proximity to the governor's residence afforded him friendship and social interaction with successive leaders of the colony, another relationship with much greater impact soon began. A friend and professor at the College of William and Mary, William Small, introduced Wythe to a bright student named Thomas Jefferson and the three frequently attended social events at the Palace together. Jefferson lived and studied with Wythe for five years until he passed the bar in 1767, and was able to secure a position as clerk in the House of Burgesses just as his mentor had. The following year Wythe was elected mayor of Williamsburg and also appointed to the board of William and Mary. It was at this time that friction began to develop between Wythe and British leadership, beginning with the arrival of a new Royal Governor, Baron de Botetourt, who dissolved the House of Burgesses by order of the Crown in 1768. Although the action was met with protest from the members, Botetourt was still a popular enough leader and when he died in 1771 his funeral was impressive. The same could not be said for his replacement, the Earl of Dunmore, whose frequent clashes with Wythe pushed the latter to distance himself from royalists and assert the colonists' right to self-government. When fighting began with the battles of Lexington and Concord, Wythe volunteered to fight but was instead sent to Philadelphia to join four other Virginians at the Continental Congress. Although he supported the vote for independence that was held on July 4 he was no longer present when the document was signed on August 2, as he had travelled back to Williamsburg to help form the new state government. Wythe's fellow Virginians respected him so highly that they deliberately left room for him to later sign at the top of their group.

George Wythe returned to Virginia and was selected to a group responsible for revising the state's legal code. He was elected to the House of Delegates in 1777 and was quickly named the assembly's Speaker, and the following year he was named as once of three original Chancellors for the state where he used his influence to attack the institution of slavery. At the same time, he assisted in writing the state constitution and creating the official Seal of Virginia, one of three he designed during his life alongside those of Virginia's High Court of Chancery and the College of William and Mary. In 1779, Governor Thomas Jefferson was involved in creating the nation's first Professor of Law position at the College of William and Mary, which Wythe assumed and would eventually teach such luminaries as James Monroe, John Marshall, and Henry Clay. Virginia sent Wythe to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, but once again he was not present to sign the completed document as he resigned his position to return home and care for his wife, Elizabeth, who died shortly thereafter. Although former allies Patrick Henry and George Mason opposed ratification, Wythe was able to persuade the majority to support its passage. He resigned his college position in 1789 after a dispute with their leadership and a relocation of the state capitol to Richmond, where he moved to continue his judicial duties. His increasing opposition to slavery led him to free many that he owned at the time of his wife's death, and he was ridiculed by many when he chose to pay those who remained. His moral character and generosity, unfortunately, became contributing factors in his death. Wythe originally wrote in his will that his estate would be divided between a grandnephew that had come to live with him, George Sweeny, and a former slave named Michael Brown. According to a housekeeper named Lydia Broadnax, Sweeny managed to poison food that she had eaten along with Brown and Wythe. Broadnax survived but both men died, and charges against Sweeny were dismissed because Lydia's testimony was not allowed in court due to her status as a former slave. On his deathbed, Wythe was able to change his will to completely write out his murderous grandnephew before passing away at the age of 80.

The signature of George Wythe can be found as the sixth name on the third column beneath the Declaration of Independence.

Comments

Post a Comment