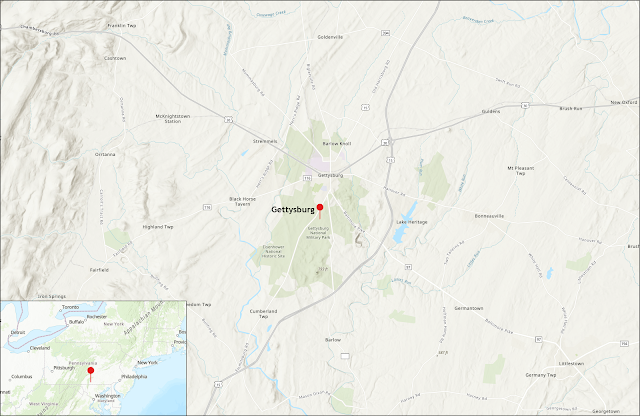

Geography of War - The Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg (American Civil War)

Date:

July 1-3, 1863

July 1-3, 1863

Modern Location:

South central Pennsylvania, United States

Combatants:

Union Army of the Potomac (led by General George G. Meade) vs. Confederate Army of Northern Virginia (led by General Robert E. Lee)

Summary:

Just two years into the Civil War, the vast majority of fighting had taken place in the southern states. Confederate forces had only made a single large-scale advance onto Union soil, which had ended with a stinging defeat at Antietam in September, 1862. After a string of successes culminating in a decisive victory at Chancellorsville, Gen. Robert E. Lee hoped to move his army into Pennsylvania to finally win a meaningful battle in the North, perhaps to stoke growing sentiment among the Union population to make peace with the Confederates and end the war that had already caused over 200,000 casualties. The newly-appointed commander of the Union army was Gen. George G. Meade, replacing Gen. Joseph Hooker after the latter proved unequal to the task of stopping Lee. Meade's goal was to protect Washington D.C. from Confederate forces, even as they moved through Maryland and into Pennsylvania, and he moved to engage Lee. Upon hearing of the Union advance the three corps of the southern army intended to gather their full strength and prepare for battle, but as the first units of Confederates approached a crossroads town in search of supplies they encountered northern cavalry scouts that had already arrived. That town's name was Gettysburg, and it would become the host to the bloodiest battle in American history.

Early on the morning of July 1, the first shots of the battle were fired as units of each army quite literally bumped into one another on the northwest side of the city. The amassed Confederate forces successfully drove the outnumbered Yankees away from the battlefield, through the city, and into the hills south of town. Lee had insufficient intelligence on the makeup of the force he faced, due in part to his cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart having flanked the Union army to the east but not yet reconnected with the main army, and therefore did not insist that the attack continue although he had superior numbers. The delay allowed Union reinforcements to arrive and set up a defensive position overnight, shaped like a tight fishhook, around which the now-outmanned Confederate army gathered and initiated their attacks. July 2 saw some of the most brutal fighting of the war take place, as Lee ordered attacks against his enemy's right and left flanks. Confederates advanced from their positions along Seminary Ridge to the west against the southern end of Meade's position at Little Round Top, while at the northeast end of the battlefield an intense struggle was waged for control of Culp's Hill. With over 150,000 soldiers on the field, troop movements for each army frequently involved 10,000 or more men, and Meade's enclosed position allowed for more efficiency and better intelligence than Lee's sprawling line. In a move that was uncommon during the Civil War the southern attackers continued their charges deep into the night, but eventually the second day of battle ended with Union forces continuing to hold their high ground on both flanks. July 3 began with renewed efforts to wrest Culp's Hill away from northern control, before a massive charge was ordered by Lee into the center of the Union line. Starting in the early afternoon a massive artillery barrage from the Army of Northern Virginia, well over 12,000 Confederates attempted to cross a mile of field from Seminary Ridge to Cemetery Ridge. Meade had correctly predicted the move, and had stationed his own heavy artillery to meet the onslaught. Pickett's Charge, as the fateful advance became known, managed to cross the open terrain in the face of heavy cannon and musket fire but was not able to pierce the Union line. Although the assault was likely the farthest that southern forces would advance during the course of the war, it was ultimately a failure as fewer than half of the troops made the return trip to the Confederate lines. Several miles east of the battlefield a number of cavalry engagements took place and the Union forces were able to hold off their exhausted attackers, effectively preventing any further attacks against the defensive right flank. The battle was over, although the armies remained on the field during July 4 as Lee anticipated a counterattack that never came. That evening he finally retreated, never again to advance onto Union soil.

View of the battlefield from above Lee's headquarters (Seminary Ridge along the right, Little Round Top in the background, and Culp's Hill to the left):

Geography:

Gettysburg may have been an accidental battlefield, with neither side lying in wait for the other to arrive, but its very location on the Union side of the war made it significant. Its position as a crossroads between many towns may well have led to it being the place where opposing forces eventually came into contact, and the presence of defensible hills on the south side of town caused Meade and his generals to favor making their stand here rather than retreating farther south into Maryland. There are several important features on the battlefield that remain visible today, starting with the three most important hills. Culp's Hill, Cemetery Hill, and Little Round Top were all fiercely contested positions that the Union successfully held - losing any one of these may well have compromised the rest of Meade's troops and forced a retreat. The two opposing battle lines were formed along the raised positions of Seminary Ridge and Cemetery Ridge, while the broad no-man's land between them formed the unsheltered ground across which Pickett's Charge struggled to advance. Early skirmishes along the southern end of the battlefield created the settings for intense fighting at locations known as Wheatfield, Peach Orchard, and Devil's Den - a rocky hill beside Little Round Top that exchanged hands frequently over the course of the battle.

Result:

After three days, each side suffered over 23,000 casualties, which accounted for 28% of the Army of the Potomac and 37% of the Army of Northern Virginia. Of the 120 generals who were present at Gettysburg, nine died on the field and another died during the southern retreat. It was a massive defeat for Gen. Lee and the Confederacy as it quelled much of the anti-war sentiment that had been building in the North and, alongside the surrender of Vicksburg on the same day, virtually assured that recognition of the Confederate States of America by European nations (let alone their support and intervention) would not be forthcoming. The Union believed they had found a general in Meade who could match the previously-invincible Robert E. Lee, and he was not replaced as the head of the Army of the Potomac for the duration of the war. His inability to continue the pursuit of the southern forces as they escaped back into Virginia drew heavy criticism, and some blamed him for allowing the war to continue. Nevertheless, the battle is generally considered to be the major turning point in the Civil War that directly led to the survival of the Union, and the Gettysburg Address that President Lincoln gave to commemorate the Soldiers' National Cemetery was not only widely applauded at the time but is now remembered as one of the greatest speeches in American history.

Comments

Post a Comment