Galveston County - Bolivar Peninsula

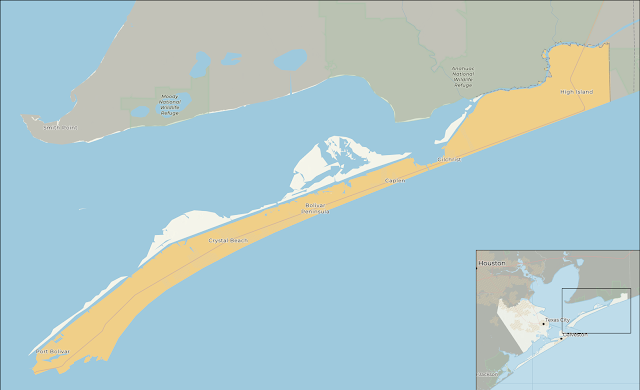

So far all of our stops in Galveston County have been focused on the west side of the bay. There is, however, a rich history on the east side that still deserves attention. Bolivar Peninsula sits just across from Galveston Island, and is home to 2,769 residents according to the US Census Bureau's 2020 count. The peninsula that varies in width from nearly 3 miles to barely 600 yards across stretches for 27 miles between the Gulf of Mexico to the south and East Bay to the north, until it reaches the mainland at Galveston County's border with neighboring Chambers County. Several communities are strung out along Highway 87, the main road that serves Bolivar - including Port Bolivar, Crystal Beach, Caplan, Gilchrist, and High Island - and we'll visit them all as a group.

The history of Bolivar Peninsula, like so many other areas along the Texas coast, begins with a number of the tribes that frequented the area long before Europeans began exploring. In addition to the Karankawas that we've discussed in other posts, this land was also visited by the Orcoquisas and the Atakapas which have each left their legacies in the form of burial grounds and scattered artifacts. Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca was the first historian to tell the history of Texas as he was shipwrecked near the entrance to Galveston Bay in 1528, and the location of his landfall may have actually been along Bolivar Peninsula rather than the presumed area of Galveston Island. Nearly 200 years later, French explorer Simars de Belle Isle was accidentally left on Galveston and was captured by Orcoquisa Indians based on Bolivar. He would later accuse his captors of practicing cannibalism during his captivity, but that may well have been an exaggeration as historians have largely dismissed the assertion due to a lack of evidence that such practices took place.

During the early 19th century, the pirate Jean Lafitte established a local presence in the area and built a town he named Campeche on Galveston Island. His crew would use the peninsula for parties, and his cabin boy would eventually build a home at the northern end near today's High Island community. Bolivar, which was named after the anti-Spanish mastermind General Simon Bolivar, continued to be a hub of revolutionary and smuggling activity throughout the years leading up to Texas independence. It was used as the overland path to take slaves from Galveston to New Orleans, and a number of Spanish rebels constructed a simple fort at Bolivar point for a base of operations. General James Long brought his family and a number of soldiers there in 1820 and constructed Fort Las Casas, but when he and the majority of his forces departed the following year for Goliad he left behind his pregnant wife, Jane, along with their daughter Ann, a slave girl named Kian, and a small guard of soldiers. When James Long did not return, everyone except Jane, Ann, and Kian eventually abandoned the fort. After 11 months, during which time she had given birth to another daughter, Jane finally left Bolivar. She believed her child was the first Anglo baby born in Texas, and although that wasn't actually the case she still became known to many as the Mother of Texas.

It wasn't until two years after Texas independence that Bolivar's first permanent settler arrived, Samuel Parr, who began the far-western community that eventually became known as Port Bolivar. Farther to the east, the skinniest portion of the peninsula became known as "Rollover" because it was a favorite location for smugglers to roll their cargo across the land to avoid costly tariffs. The Point Bolivar Lighthouse was built in 1852, then dismantled and turned into cannonballs by Confederate troops defending Bolivar, before being rebuilt in 1872. The economy throughout the latter half of the 19th century was farming and ranching, and by 1880 Bolivar became known as the Watermelon Capital of Texas due to the large output of their cash crop. In the years before the 20th century dawned the beaches had begun to attract the attention of wealthier citizens of Beaumont, and by 1896 the Galveston and Interstate Railroad had constructed a new line across the island as well as the Sea View Hotel to attract tourists.

As with other coastal communities, the morning of September 8, 1900 drastically changed the fortunes of Bolivar Peninsula as the great hurricane destroyed most inhabitable structures. The lighthouse survived, saving the lives of 125 individuals inside. The devastation was nearly complete, however, and the area was promptly evacuated. The G&I Railroad lost a train and 30 miles of track, but after three years of massive community effort they were able to fund the rebuilding of the line, as well as the repair of the original engine and several coaches that had been buried in sand. Roughly a dozen of the original passengers that began the trip in 1900 came to finish their journey in 1903, famously making the longest train ride in history a total of 3 years, 16 days, and 10 minutes late to its destination.

The success of the Houston Ship Channel did nearly as much to cripple growth as the hurricanes had, and although ferry service to Galveston began in 1933 it was too late to revive the industrial prospects of Bolivar Peninsula. Train service beyond High Island was abandoned as roads began to appear (interestingly, the beach was the only "road" on Bolivar until 1930), and eventually tourism and recreation became the primary economic drivers. With only two ways to arrive - the ferry to the west and a single highway to the east - many residents have been attracted over the years to the relative seclusion that is rare so close to a major metropolitan area. The communities along the peninsula remain small, although the largest town of Crystal Beach was incorporated for a time during the 1970s and 1980s, but they have proven themselves to be resilient in the face of continued tropical threats through the years. In spite of repeated damage from storms such as Hurricane Ike in 2008, residents continue returning and rebuilding this thin ribbon of beach that they've come to enjoy and call home.

Comments

Post a Comment